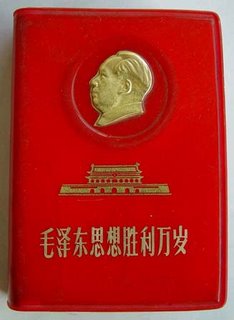

Little yellow books

Scan This Book! Kevin Kelly in the Times magazine: When Google announced in December 2004 that it would digitally scan the books of five major research libraries to make their contents searchable, the promise of a universal library was resurrected. Indeed, the explosive rise of the Web, going from nothing to everything in one decade, has encouraged us to believe in the impossible again. Might the long-heralded great library of all knowledge really be within our grasp?

Brewster Kahle, an archivist overseeing another scanning project, says that the universal library is now within reach. "This is our chance to one-up the Greeks!" he shouts. "It is really possible with the technology of today, not tomorrow. We can provide all the works of humankind to all the people of the world. It will be an achievement remembered for all time, like putting a man on the moon." And unlike the libraries of old, which were restricted to the elite, this library would be truly democratic, offering every book to every person. ...

Like many other functions in our global economy, however, the real work has been happening far away, while we sleep. We are outsourcing the scanning of the universal library. Superstar, an entrepreneurial company based in Beijing, has scanned every book from 900 university libraries in China. It has already digitized 1.3 million unique titles in Chinese, which it estimates is about half of all the books published in the Chinese language since 1949. It costs $30 to scan a book at Stanford but only $10 in China.

Raj Reddy, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University, decided to move a fair-size English-language library to where the cheap subsidized scanners were. In 2004, he borrowed 30,000 volumes from the storage rooms of the Carnegie Mellon library and the Carnegie Library and packed them off to China in a single shipping container to be scanned by an assembly line of workers paid by the Chinese. His project, which he calls the Million Book Project, is churning out 100,000 pages per day at 20 scanning stations in India and China. Reddy hopes to reach a million digitized books in two years.

The idea is to seed the bookless developing world with easily available texts. Superstar sells copies of books it scans back to the same university libraries it scans from. A university can expand a typical 60,000-volume library into a 1.3 million-volume one overnight. At about 50 cents per digital book acquired, it's a cheap way for a library to increase its collection. Bill McCoy, the general manager of Adobe's e-publishing business, says: "Some of us have thousands of books at home, can walk to wonderful big-box bookstores and well-stocked libraries and can get Amazon.com to deliver next day. The most dramatic effect of digital libraries will be not on us, the well-booked, but on the billions of people worldwide who are underserved by ordinary paper books." It is these underbooked — students in Mali, scientists in Kazakhstan, elderly people in Peru — whose lives will be transformed when even the simplest unadorned version of the universal library is placed in their hands.It's not a very good article--Kelly tries too hard to either stretch and draw grand conclusions, or shoehorn his theories into the piece--but these few paragraphs are interesting. For people who pooh-pah the idea of peasant China challenging the U.S. in our lifetime, it's a reminder that technology makes possible giant acts of leapfrogging.

So instead of taking years to erect telephone poles and string wires, China's just going directly to cell phones for everyone. Likewise, there's no need for a Chinese Carnegie to jump-start decades of library building; just scan and distribute via the Web.

You can't apply this to everything, obviously, and I think Americans have this irrational and racism-based fear of a yellow tide sweeping over us that makes it easy to see China, like the USSR, as a potential peer, rather than for what it is: A giant country that is going to be buffeted by technological change more than almost any other nation, and that faces many distinct futures.

In the best case scenario, it remains intact, tamps down economic inequalities, taps into the natural gifts of its populace and culture, and emerges as a democratic counterpart and counterweight to America in Asia.

Worst case all hell breaks loose and all the book learning in the world won't be able to civilize China's armies of millions of angry young men.

Image of Mao's Little Red Book via Chinese furniture importer Zitantique

No comments:

Post a Comment